While often simplified as “elephant rage,” musth is a sophisticated physiological state driven by a hormonal surge that has no direct parallel in other mammals. For a bull elephant, this period is a high-stakes biological gamble that prioritizes reproduction over self-preservation. Understanding the intricate elephant musth physiology and symptoms is essential for researchers, mahouts, and conservationists alike.

To see how these hormonal surges fit into the elephant’s broader biological framework, explore our Comprehensive Guide to Elephant Physiology and Health.

1. The Hormonal Catalyst: Testosterone and Cortisol

The primary driver of elephant musth physiology and symptoms is a staggering increase in testosterone. During peak musth, a bull’s testosterone levels can reach up to 60 times their baseline, sometimes exceeding 100 ng/mL in serum.

However, 2026 research has highlighted the critical role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal (HPI) axis. Unlike typical stress responses, cortisol often increases alongside testosterone during musth. This dual-hormone elevation allows the elephant to maintain high energy levels despite a significant reduction in food intake. This specific metabolic shift is a hallmark of elephant musth physiology and symptoms, effectively turning the bull into a biological “sprinting machine” for several months.

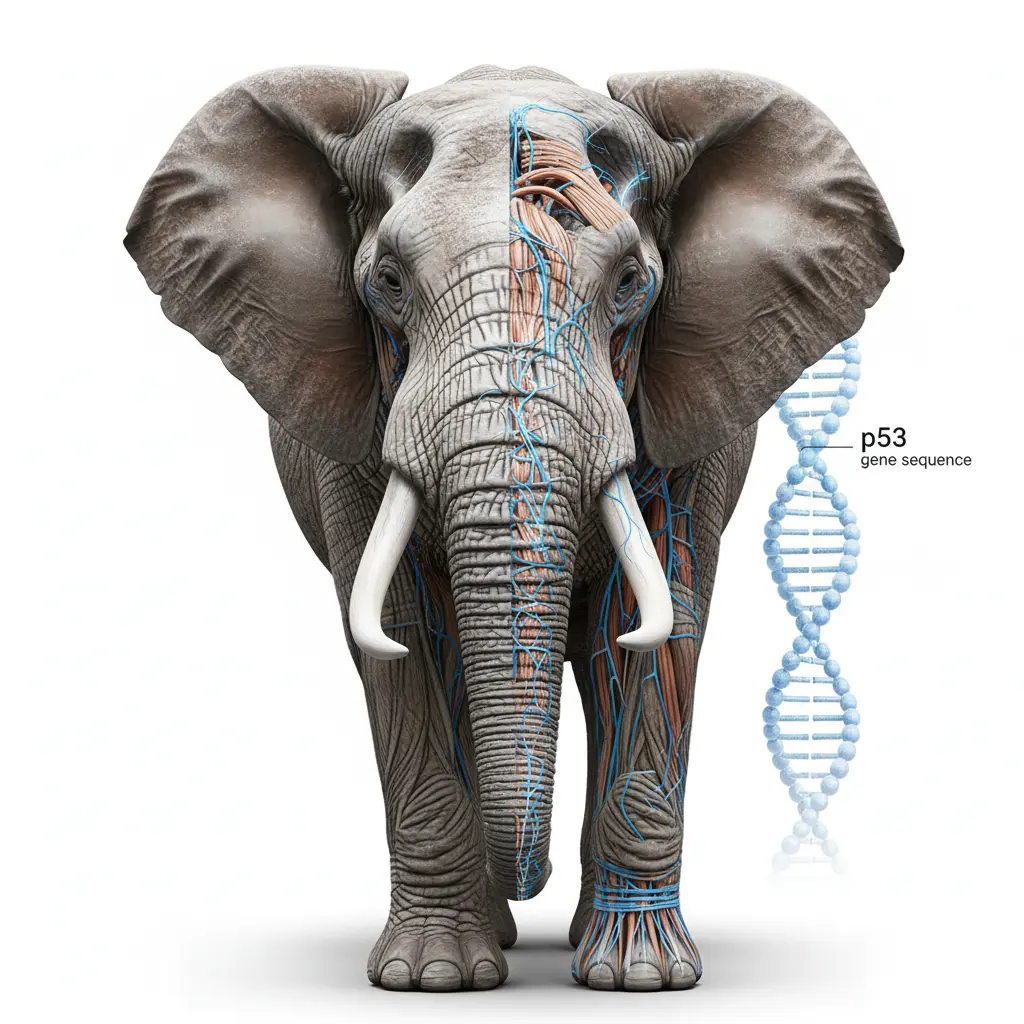

2. Recognizing the Physical Indicators: Temporal Glands and Urine Dribbling

The most visible elephant musth physiology and symptoms are the physical “signals” sent to the rest of the herd.

- Temporal Gland Secretion (TGS): Located between the eye and ear, the temporal glands swell and secrete a thick, pungent, tar-like substance known as temporin. This secretion contains volatile compounds like frontalin, which act as a chemical broadcast of the bull’s status.

- Urine Dribbling (UD): A musth bull will continuously dribble urine, often reaching up to 300 liters a day. This is not a lack of bladder control but a deliberate “scent trail” that advertises his presence to estrous females and warns away subordinate males.

According to 2025 longitudinal studies published in MDPI, the onset of TGS typically precedes the most intense behavioral changes, serving as an early warning system for the bull’s transition into a high-androgen state.

3. Behavioral Shifts: The Psychology of Intoxication

The term “musth” is derived from the Urdu word for “intoxicated,” which accurately describes the psychological impact of elephant musth physiology and symptoms.

The heightened aggression associated with musth is an androgen-mediated response designed to override the standard social hierarchy. Even a mid-ranking bull in musth can intimidate a larger, older non-musth bull. Symptoms include:

- Unpredictability: A sudden shift from calm foraging to focused chasing.

- Reduced Appetite: Bulls in musth may lose up to 10% of their body mass as they prioritize searching for mates over feeding.

- Heightened Sensitivity: Extreme irritability toward sounds, movements, and the presence of other males.

4. Captive vs. Wild Management: A 2026 Perspective

Managing elephant musth physiology and symptoms in a captive environment, such as a zoo or sanctuary, presents a unique set of challenges. In the wild, younger bulls are often “suppressed” by the presence of older, dominant musth bulls—a natural regulatory system.

In captivity, without these social suppressors, young bulls may enter musth earlier and with more intensity. Modern management in 2026 focuses on “protected contact” protocols and diet modification to manage the metabolic “fire” of musth without compromising the animal’s welfare.

5. The Necessity of the Surge

While dangerous, the elephant musth physiology and symptoms are indicators of a healthy, mature bull. It is a period of peak biological performance that ensures the strongest genes are passed to the next generation. By studying the chemical composition of temporin and the fluctuations in fecal androgen metabolites, we can better predict these cycles and ensure the safety of both elephants and the humans who care for them.