While humans perceive elephants through their thunderous trumpets, their most profound conversations happen in a frequency range we cannot hear. Elephant infrasound production and anatomy allow these giants to coordinate movements across tens of kilometers, bypassing the limitations of dense forests and open savannas. In this guide, we dive deep into the “low-frequency engine” that powers the world’s most complex long-distance communication.

To understand how these vocalizations fit into the giant’s overall biological map, visit our Guide to Elephant Physiology and Health.

1. The Larynx: A Low-Frequency Musical Instrument

The primary site for elephant infrasound production and anatomy is the larynx. For years, scientists debated whether elephants “purred” (active muscle contraction) or “sang” (flow-induced vibration).

Research confirmed that elephants use the same physical principles as human singers the myoelastic-aerodynamic (MEAD) mechanism. However, the sheer scale of the elephant larynx allows for frequencies as low as 10–20 Hz.

- Vocal Fold Mass: Elephant vocal folds are roughly 8–10 cm long—eight times longer than a human’s.

- Passive Vibration: When air from the lungs passes through these massive folds, they vibrate at a fundamental frequency below the threshold of human hearing (20 Hz).

- The “Fifth Limb” Extension: By extending their trunk, elephants can further lengthen their vocal tract, lowering the “formants” or resonant frequencies of the sound even further.

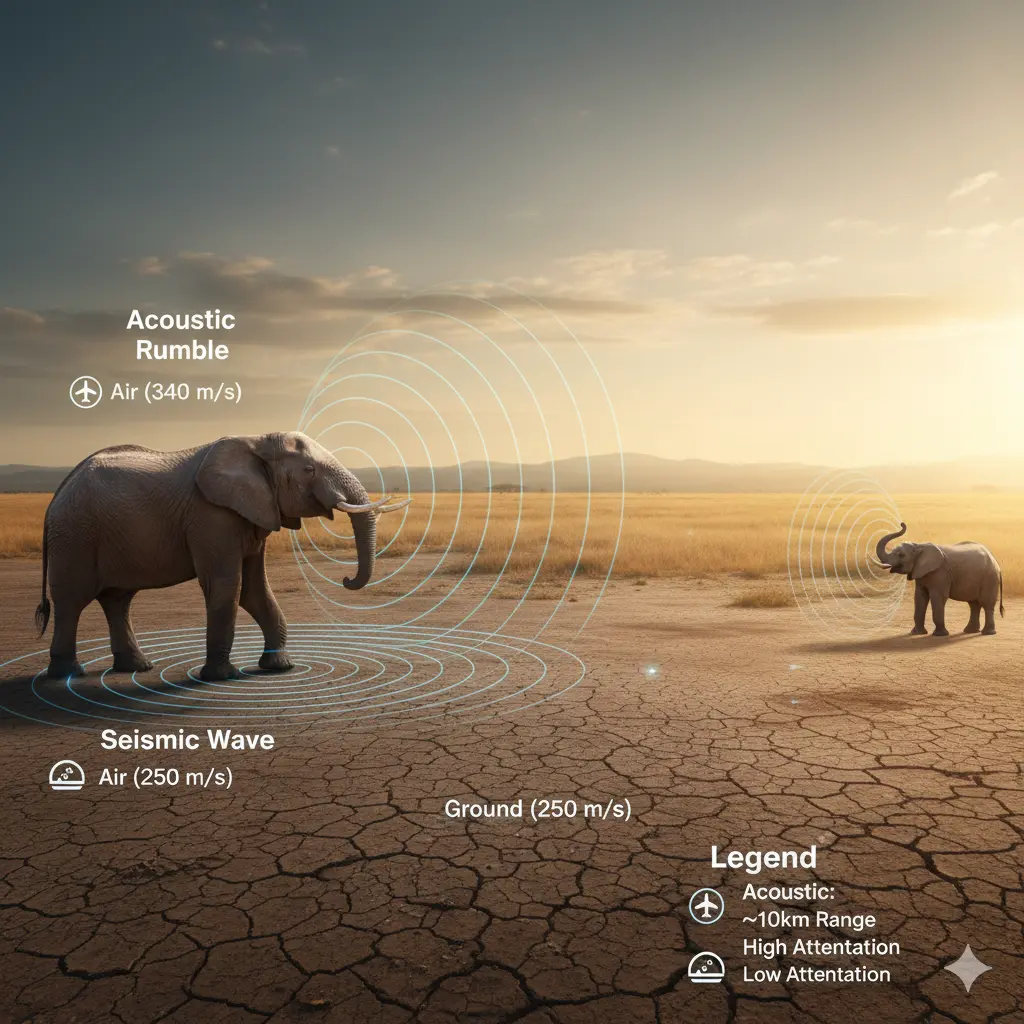

2. Acoustic vs. Seismic: Two Channels of Infrasound

A fascinating aspect of elephant infrasound production and anatomy is that the sound doesn’t just travel through the air; it couples with the earth.

| Communication Channel | Propagation Medium | Estimated Range |

| Acoustic Rumble | Air (343 m/s) | up to 10 km |

| Seismic Wave | Ground (250-280 m/s) | up to 32 km |

When an elephant rumbles, it creates “Rayleigh waves” that travel through the soil. 2026 bioacoustic studies have shown that elephants can actually distinguish between different individual callers based solely on these ground-borne vibrations. This dual-channel system is a hallmark of elephant infrasound production and anatomy, providing a “private” network that predators cannot monitor.

3. Receiving the Signal: Pacinian Corpuscles and Bone Conduction

Elephant infrasound production and anatomy isn’t just about making noise; it’s about the specialized hardware required to “hear” with more than just ears.

The Foot as a Satellite Dish

Elephants possess highly specialized mechanoreceptors called Pacinian corpuscles in the dermis of their feet and the tip of their trunks. These receptors are sensitive to microscopic vibrations.

- Triangulation: By lifting one foot or leaning forward to increase pressure on their front legs, elephants can “triangulate” the source of a distant seismic rumble.

- Bone Conduction: Vibrations travel from the ground, through the massive leg bones (acting as acoustic conductors), and directly into the middle ear. This bypasses the eardrum entirely, allowing the elephant to “feel” a conversation from kilometers away.

4. The Social Impact of Infrasonic Rumbles

The complexity of elephant infrasound production and anatomy serves a vital social purpose. Stanford University research (2024/2025) identified specific “let’s go” rumbles that matriarchs use to initiate herd movement.

Without the elephant infrasound production and anatomy required for these low-frequency calls, fission-fusion societies (where groups split and reunite) would collapse. These rumbles convey identity, reproductive status (musth or estrus), and urgent warnings about distant threats like lions or human poachers.

Watch: How Elephants Listen With Their Feet

5. Protecting the Silent Frequency

As human-generated noise pollution increases, the “quiet zone” required for elephant infrasound production and anatomy to function is being threatened. Understanding the mechanics of the larynx and the sensitivity of the elephant foot is no longer just a biological curiosity—it is a conservation priority for 2026.