The Ideal Parent Figure (IPF) Protocol — a guided-imagery, attachment-focused intervention developed by Daniel P. Brown and colleagues — has gained visibility in trauma-informed and attachment-focused clinical circles over the past decade. It isn’t a pop-psychology trick; IPF sits inside a broader “Three Pillars” treatment model and has been evaluated in clinical settings, most notably as a stabilization tool for adults with complex trauma and attachment disturbances. Below I summarize the strongest pieces of evidence and the clinical rationale that support IPF, and point out where the research base still needs to grow.

What IPF is and why it should be testable

At its core, IPF uses repeated, therapist-guided visualization exercises in which clients imagine caregiving figures who reliably provide the five core attachment experiences: protection/safety, attunement/being seen, soothing/comfort, delight/value, and encouragement/support for the client’s best self. The theoretical premise is straightforward: the mind and nervous system encode imagined experiences in ways that can shift internal working models formed in childhood, especially when those imaginal experiences are repeated and paired with felt safety in therapy. This makes IPF a clear, testable intervention grounded in attachment theory and experiential mechanisms.

Clinical pilot data: stabilization in CPTSD

One of the most commonly cited empirical supports for IPF is a pilot study conducted in France that evaluated the method as a short stabilization treatment for adults with CPTSD and histories of childhood trauma. In that uncontrolled pilot (n ≈ 17), a brief course of IPF sessions produced statistically significant reductions in symptom scores and improvements in quality of life; improvements were reportedly sustained at follow-up several months later. While the study is limited by small sample size and lack of a control group, it is important because it operationalized IPF in a clinical trial context and demonstrated feasibility and promising effect sizes in a highly symptomatic population.

Mechanisms supported by broader research

IPF’s hypothesized mechanisms — repeated corrective emotional experiences, imagery-based memory reconsolidation, and bottom-up regulation of the nervous system — are consistent with established findings in related literatures. Research on imagery techniques, memory reconsolidation, and attachment-focused interventions shows that imagined caregiving experiences can shift self-representations and affect regulation when practiced repeatedly and combined with therapeutic containment. In short: even when evidence specifically for ideal parent figure protocol is limited, its mechanisms are consistent with empirically supported processes in psychotherapy.

Clinical uptake and practitioner reports

Beyond formal trials, IPF has been disseminated via Brown & Elliott’s clinical manual and book, professional trainings, and published clinical descriptions. Many trauma-informed clinicians now integrate IPF into stabilization phases, often alongside somatic work, EMDR, Internal Family Systems, or metacognitive training. Practitioner reports and clinical case series describe reliable gains in clients’ capacity for self-soothing, decreased reactivity in relationships, and improved capacity to receive care — outcomes consistent with attachment repair. These clinical data are lower on the evidence hierarchy than randomized trials, but they are valuable for establishing external validity and informing next-step research questions.

Strengths of the current evidence

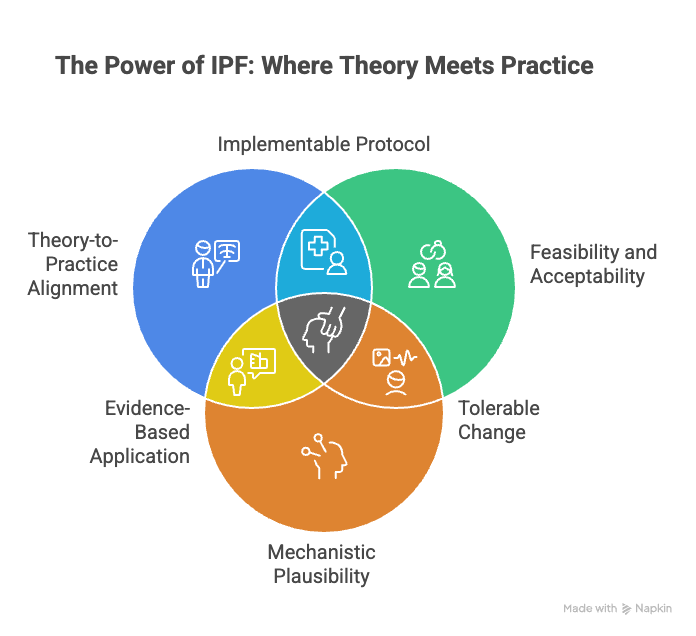

- Theory-to-practice alignment: IPF maps directly onto attachment theory and offers concrete exercises clinicians can implement (helpful for treatment fidelity and replication).

- Feasibility and acceptability: Pilot data and clinical reports suggest that clients can learn and tolerate the protocol, even in populations with significant developmental trauma.

- Mechanistic plausibility: The intervention targets well-described processes (internal working models, emotion regulation) that are known to be changeable through repeated corrective experiences and imagery-based work.

Limitations and gaps that matter

- Small trials and limited RCT data: To date there are promising pilot studies and clinical reports but few (if any) large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) directly testing IPF against active comparison treatments. This limits causal claims about its specific efficacy.

- Heterogeneous implementations: Clinicians sometimes adapt the protocol (session length, integration with other modalities), which complicates comparisons across studies and calls for manualized, fidelity-checked trials.

- Mechanistic measurement: More studies that measure mediator variables — e.g., shifts in attachment style, physiological markers of regulation, or neural changes — would strengthen claims about how IPF produces change.

Where the field should go next

To move IPF from promising clinical innovation to a firmly evidence-based intervention, the field needs: (a) larger randomized trials with active comparators and long-term follow-up, (b) standardized treatment manuals and fidelity checks, and (c) mechanistic studies incorporating physiological and neurobiological outcomes. These steps will clarify who benefits most, what dose is required, and how IPF compares with or complements other attachment-focused therapies.

Practical takeaway

If you’re a clinician interested in attachment repair, IPF is a theoretically coherent, clinically usable method with encouraging pilot data and broad practitioner uptake. For researchers, IPF presents a ripe opportunity: it’s concrete, manualizable, and anchored to testable mechanisms — exactly the kind of intervention that benefits from rigorous trials. Until larger RCTs appear, IPF should be considered a promising, evidence-informed tool rather than a fully validated standalone treatment.